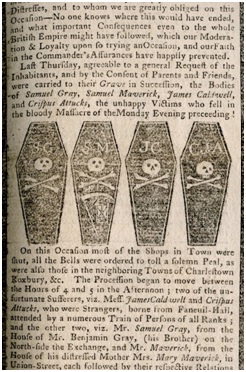

Paul Revere’s engraving, “The Bloody Massacre,” is part of Boston Public Library’s “Colonial and Revolutionary Boston”, one of Digital Commonwealth’s “Collections of Distinction”.

Scholars agree that Revere copied the arresting image in “The Bloody Massacre” from an engraving by Henry Pelham entitled “Fruits of Arbitrary Power, or the Bloody Massacre” (1770). Pelham wrote to Paul Revere complaining about the theft of his intellectual property. “If you are insensible of the Dishonour you have brought on yourself by this Act, the World will not be so.” (Clarence Brigham, “Boston Massacre, 1770, ” Paul Revere’s Engravings (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1954) ) .

While Henry Pelham may have felt that Paul Revere would be chastened for his appropriation of another man’s work, the world felt otherwise. “Certain it is that Revere was an outstanding patriot and saw the opportunity of furthering the patriot cause by circulating so significant a print.”(Brigham, p. 56).

Pelham, the artist who first rendered the image, was a Loyalist. In a letter to his sister-in-law, Susanna, the wife of John Singleton Copley, he wrote “Now we see this Country arming themselves and unsupported by any foreign Power ungenerously Waging War against their great Benefactors, and endeavouring to Ruin that State to whom they owe their being. . . “ ( Letters and Papers of John Singleton Copley and Henry Pelham, 1739-1776 , Massachusetts Historical Society, 1914, p. 344) The Copleys had left Boston for England in 1774, and Henry would follow them in 1776.

Call to Arms or Lamentation?

On the one year anniversary of the Boston Massacre, Paul Revere put together a striking exhibit in the windows of his home, displaying work depicting the “Tyranny of the British Administration of Government.” “The Bloody Massacre” was included in the illuminated display. The Boston Gazette reported that “the Spectators, which amounted to many Thousands, were struck with solemn Silence, and their Countenances covered with a melancholy Gloom.”

Goya’s monumental work, “The 3rd of May 1808” has been compared with Paul Revere’s engraving. While the scale of the works is very different, the subject matter and the composition are very similar. The 82 prints in Goya’s series, Los desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War), published 35 years after Goya’s death, argue that Goya was painting about the horrors of war, not trying to create propaganda. Paul Revere’s engraving poses more of a question, asking his fellow citizens to respond. “The prints were intended as propaganda. . . “( Beyond Midnight: Paul Revere, American Antiquarian Society online resource, 2020).

Say Their Names, compassion for the victims

Samuel Gray. Samuel Maverick. James Caldwell. Crispus Attucks. These men were victims of members of a British regiment on King Street in Boston on March 5, 1770. James Caldwell and Crispus Attucks had no family or home in Boston, and Samuel Adams organized a procession to transport their caskets to Faneuil Hall, where they lay in state for three days before their public funeral. The people of Boston held a funeral procession for all of the victims, and they were buried in Boston in the Granary Burying Ground.

Crispus Attucks was a sailor of mixed African and Indigenous ancestry. The significance of his death has been a matter of debate for the last 250 years, argued in three different intertwining threads:

- He was the leader of a mob. This was John Adams’s argument in a Courtroom in 1770 when he defended William Wemms and seven other British soldiers. Adams described Attucks as “a stout Molatto fellow, whose very looks, was enough to terrify an person” (Adams Papers, Digital Edition, volume 3, p. 269, Historical Society) . This was also the (unsuccessful) position of the Massachusetts Historical Society when they opposed a monument to Attucks on the Boston Common in 1887 (Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Second Series, Vol. 3, [Vol. 23 of continuous numbering] (1886 – 1887), pp. 313-318).

- He was an African American hero who should be acknowledged and memorialized. This was William C. Nell’s argument when he advocated for an annual celebration of Crispus Attucks Day on March 5 and wrote The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution in the 1850s.

- He was an American hero. John Boyle O’Reilly’s poem at the 1888 dedication of the memorial on the Boston Common (p.56) captures the idea that Crispus Attucks represented all Americans:

“And so must we come to the learning of Boston’s lesson to-day

The moral that Crispus Attucks taught in the old heroic way,

God made mankind to be one in blood, as one in spirit and thought. . . “

from the Digital Commonwealth Statement of Values, Adopted by the Board on October 19, 2021.

“The study of history can be an effective tool against racism and can support better understanding of the experience of Black people. However, archives are not neutral; they are created by people and reflect the power structures that those people are influenced by and participate in. We must choose what our non-neutrality means. In this moment, we specifically affirm that Black lives matter and that we support efforts to dismantle oppression and injustice.”

from Statement from Digital Commonwealth Board on Black Lives Matter, Adopted by the Board on June 16, 2020.

Barbara Schneider, Member Outreach and Education Committee