It will come as no surprise that there is widespread, urgent demand from institutions across the state to digitize historical newspapers, especially local titles that provide invaluable local coverage of daily history and titles with underrepresented perspectives and histories. There is an incredible amount of important material in need of access and preservation, and making these resources available will require a robust, sustained effort.

The Digital Services team at BPL has been working on increasing capacity for newspaper digitization and dissemination; here’s an overview of recent efforts from the last year:

Digitization at BPL

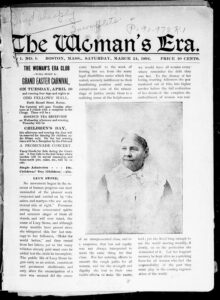

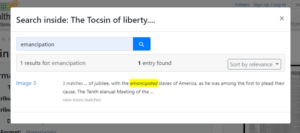

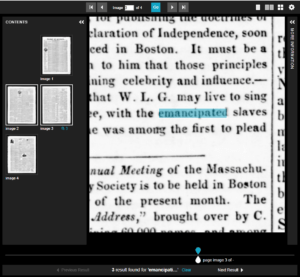

The BPL obtained a Mekel Mach 5 high-capacity microfilm scanner in March 2021, but the pandemic resulted in a significant delay with scheduling the necessary setup and training needed for operation. Mekel’s imaging technicians were finally able to help get this machine up and running in the fall of 2021, which has since been used to digitize several short runs of historically significant newspapers, including The Woman’s Era and The Tocsin of Liberty. The main current project, which is still ongoing, is scanning a major run of the Lawrence Evening Tribune (1890-1929).

While the scanning work is proceeding well (over 96,000 pages to date), imaging is only the start of any newspaper digitization project – there is significant manual work needed to collate and group the scanned pages into issue-level folders, and to identify missing pages, duplicate pages, and other anomalies.

There are also technical steps involved in processing the scanned images to create derivative files (such as using optical character recognition to extract text and word-coordinate information to support full-text searching and highlighting keyword matches on the page image), as well as developing the pipelines, workflows, and scripts to ingest the content into the digital repository. The library hopes to make significant progress on these latter steps during the second half of 2022.

National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP) Grant

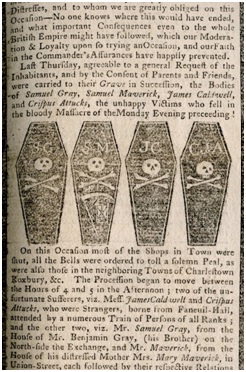

Through the assistance of the Boston Public Library Fund (https://bplfund.org/), BPL was awarded a grant in September 2021 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to join the National Digital Newspaper Program (https://www.loc.gov/ndnp/), a long-running effort coordinated by the Library of Congress to build and maintain a free online digital library of historical newspapers from all U.S. states and territories. During the last few months, Digital Services staff has been working with an advisory committee of scholars and experts to identify significant newspapers from the library’s microfilm archives for inclusion in this national collection, which will then be digitized and made available via Chronicling America (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/), which provides access to over 18 million pages from over 6,000 newspaper titles published from 1777 to 1963, and in Digital Commonwealth. The project, which will run until October 2023 and produce 100,000 pages of scanned newspaper content, is currently nearing the end of the title selection process, with imaging scheduled to contracted out to a digitization vendor in the fall of this year.

MyHeritage & Boston Neighborhood Newspapers

In 2016 BPL established a partnership with MyHeritage to provide access to BPL-held microfilm for digitization and display on their online genealogy platform, with the condition that BPL will receive a copy of all digitized page images produced. To date, this partnership has resulted in the digitization of approximately 7.5 million pages from a wide variety of Massachusetts newspapers spanning the late 1700s to the mid 1900s. However, the deliverables include the image scans only, and not any of the derivative files required to support discovery and display in Digital Commonwealth (see the “Digitization at BPL” section above). Producing the necessary derivative files at this scale will require additional capacity and funding support.

To evaluate the logistics, costs, time, and effort needed to ingest the MyHeritage-digitized materials into Digital Commonwealth, BPL is currently undertaking a pilot project using a vendor specializing in newspaper digitization to process a subset of these titles, highlighting Boston’s neighborhood newspapers. The titles selected for this project span from the mid-1800s to mid-1900s, representing many newspapers that currently have limited online availability, including the Roxbury Gazette, Hyde Park Times, East Boston Free Press, South Boston Gazette, Charlestown News, and the Dorchester Beacon, to name just a few. This project will produce approximately 170,000 pages of content; processing is scheduled to be completed by the end of June, and the goal is to integrate this content into the repository ingest workflow in the latter half of the year.

Looking Forward

The projects described above will no doubt provide increased access to historical newspaper content, but to make a significant impact, these activities need to become part of a curated, sustainable program with dedicated funding, equipment, and staff. The BPL is committed to continuing participation in Library of Congress’s NDNP program, which can be renewed every two years. The Digital Services team is also actively investigating other ways to increase capacity, including grant programs, advocating for more funding from the state legislature, adding staff to help manage digitization projects, and providing guidance to institutions that want to take on their own digitization projects. As with all things Digital Commonwealth, collaboration will be key to success!