This post was written by Patricia Feeley, BPL Collaborative Services Librarian.

For a 126-year-old organization, the Trustees of Reservations is not that well-known for its cultural heritage collections. People are often familiar with the properties they own – the Crane Estate in Ipswich, Naumkeag in Stockbridge, World’s End in Hingham or Dinosaur Footprints in Holyoke – but not the history they curate. It is easy to imagine that an organization with so much history and so wide a scope would have amassed an impressive collection.

Alison Bassett and Sarah Hayes were members of the Trustees before they began working at the Trustees’ Archives and Research Center (ARC). Alison had a background in documentary film that included researching in archives just like the one she now heads. Sarah’s background included a library science degree, cultural heritage programs and experience as a member of Digital Commonwealth’s Metadata Mob. In fact, Sarah worked on metadata for one of the Trustees’ collections as a Mobster before she was hired by The Trustees.

ARC staff knew what a terrific collection they had in their Archives and Research Center. However, it was hard for staff across the state to access easily and virtually unknown to the public. The decision was made to digitize records to preserve and promote them. The preservation work began before Digital Commonwealth (DC) was involved. But both Alison and Sarah agreed that DC would provide the next step in the process.

The Trustees wanted to have its digital collections available on a statewide site that mirrored its own statewide reach. Alison and Sarah stressed the value in having complementary Massachusetts historical collections to search on one site for images that enrich your own research when that just right image isn’t in your own holdings.

Neither is shy about why they love Digital Commonwealth:

- It’s free.

- The Digital Commonwealth staff is easy to work with and they do excellent work.

It doesn’t get much better than that. With a small staff, Alison was happy to take advantage of the larger DC staff, who could devote more time to digitization projects. For the recently added Appleton Farms collection, there were many photo albums that needed to be broken down before scanning. DC was able to do this and do it quicker than ARC staff. Alison and Sarah appreciated consulting with DC staff about which albums were most representative and which would be easiest to work with. It took about a year from first contact to seeing the Appleton Farms collection uploaded, but this was mainly due to workload issues at the Trustees.

The Trustees currently have three collections on Digital Commonwealth: Trustees of Reservations Institutional Publications, Photographs from Stevens-Coolidge Place and the Appleton Family Photo Album Collection.

The first collection is straightforward. Already, Alison has referred a staffer in western Massachusetts to the digitized Annual Reports. The staffer was thrilled to be able to do his own research and Alison was thrilled not to have to scan and send dozens of pages.

The most recent collection added, the Appleton Family Photo Album Collection, depicts the oldest continuously operating farm in America and the family that founded it in 1636. The property was turned over to the Trustees in 1998. The farm’s last heirs and residents were Francis Randall Appleton, Jr. (1885-1974) and his wife, Joan Egleston Appleton (1912-2006). Joan lived on the farm until her death.

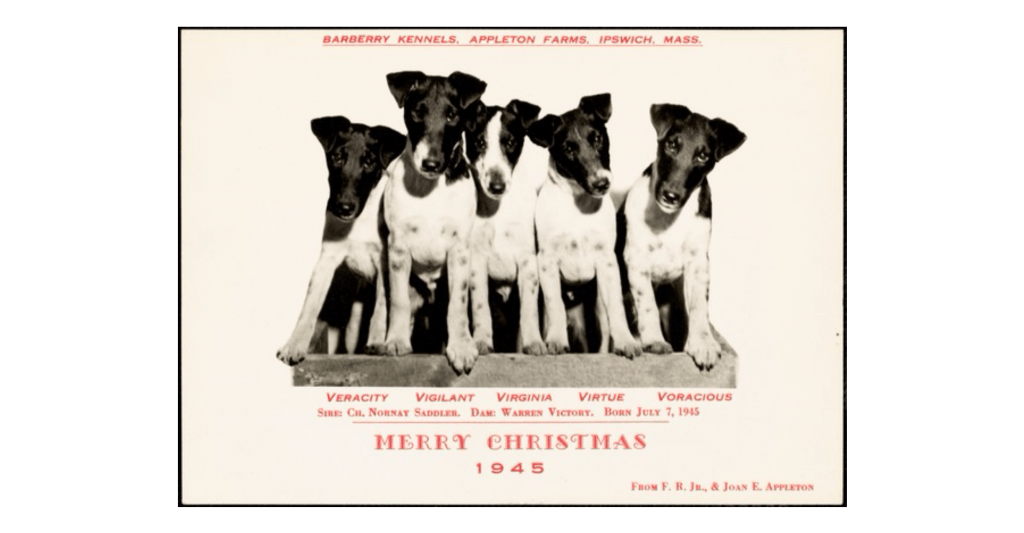

Francis Appleton was a “gentleman farmer”. His home was still a working farm, but limited in its operations. Like many gentlemen farmers of the time, Appleton sent Christmas cards showing livestock (turkeys, cows, horses) and farm scenes. The farm also ran the Barberry Kennels for a time. One Christmas card shows that year’s litter of terriers, each one’s name beginning with the letter V. One of this line would go on to win Best of Class at the Westminster Kennel Club Show.

The largest of the three collections is the Photographs from Stevens-Coolidge Place. When the ARC staff first consulted with DC, they planned to start with a smaller collection. DC staff urged them to think bigger and this collection of over 1800 images was the result.

ARC chose this collection in part because it contained a wide variety of photographic formats (daguerreotypes, tintypes, cabinet cards, cartes de visite, albumen prints, cyanotypes, collodion prints, silver gelatin prints, 35mm color prints, and Polaroids.) It also contained great photos. The families were world travelers, so the scope of the collection is broad. Also, Stevens-Coolidge Place house is usually closed to the public, so interior photographs offer access not often available.

This is also the collection that included Alison’s and Sarah’s favorite items to highlight. Alison chose a wonderfully eccentric studio portrait of an unidentified woman dressed all in black. Unlike the many other photos of women staring dreamily off into the distance, this woman looks straight back at the viewer through her monocle. Yes, monocle. She has an ungloved hand holding a Great Dane in place by her side and a gloved hand holding a cigarette. At her feet lays her other glove and what the description identifies as a “whip”, but is perhaps more of a riding crop. Either way, it is an unusual photo.

Alison admits the photo is intriguing on its own, but the ARC has no information on who the sitter is or why she chose to be depicted this way. What delights Alison is that the one clue – the photographer’s name – leads to a different historical topic. The photographer was a woman.

Emily Stokes appears in Frances Willard’s 1897 book, Occupations for Women: A Book of Practical Suggestions for the Material Advancement, the Mental and Physical Development, and the Moral and Spiritual Uplift of Women. Here we discover that Mrs. Stokes is a British immigrant to America who had been a professional photographer in Boston for 16 years at the time of publication. Child portraits are identified as her specialty. Photography is promoted as an occupation for women because it no longer involves “dangerous chemicals” or as heavy equipment as in earlier years. Ms. Willard emphasizes that electricity has made photography a good outlet for a woman’s “light touch.”

Sarah also highlights a photograph that originally seemed unremarkable, but led to a greater historical understanding of the Trustees collection. It is a portrait of the Empress Dowager Cixi. A separate project cataloguing objects in the collection led to a find of some textiles that were identified as Chinese. Additional research connected these textiles to the Empress, who was known for promoting textiles created by Chinese women. Sarah appreciates that this richer history is made possible by having these images available where connections can be made by researchers.

Alison and Sarah urge other cultural heritage organizations to take the plunge and add more collections to Digital Commonwealth.